Synopsis

Listen to the synopsis

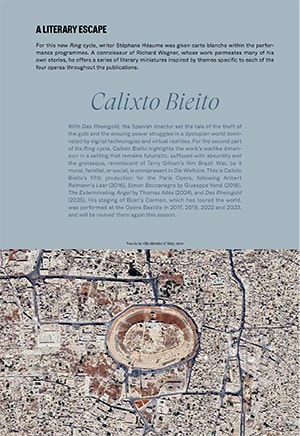

The Paris Opera continues its exploration of Richard Wagner’s colossal Ring, directed by Calixto Bieito. After the final scene of The Rhinegold, in which the gods ascend to Walhalla, The Valkyrie, the second part of the cycle, focuses on humans in the form of twins Sieglinde and Siegmund.

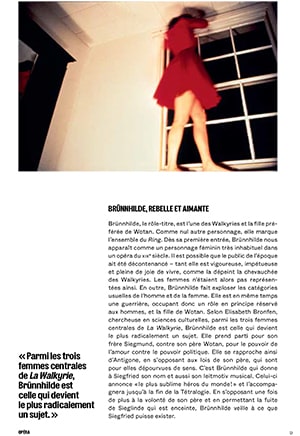

While their irrepressible, incestuous passion unleashes the wrath of Fricka, the goddess of marriage, it deeply moves the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, prompting her to defy her father, the god Wotan.

To express the power of human love, but also the contradictions of a god who wishes to engender a being who is free yet subject to his own will, Richard Wagner writes music that is by turns lyrical and sensual, fiery and heroic, like the famous “Ride of the Valkyries”.

Duration : 5h00 with 2 intervals

Language : German

Surtitle : French / English

-

Opening

-

First part 65 min

-

Intermission 45 min

-

Second part 90 min

-

Intermission 30 min

-

Third part 70 min

-

End

Artists

First evening in three acts of Der Ring des Nibelungen (1870)

Creative team

Cast

The Paris Opera Orchestra

E-doggy, chien-robot - Evotech

Die Walküre will be recorded by France Musique for broadcast on 24 January 2026 at 8 pm on the program “Samedi à l'Opéra” presented by Judith Chaine, then available for streaming on the France Musique website and the Radio France app.

Media

Access and services

Opéra Bastille

Place de la Bastille

75012 Paris

Public transport

Underground Bastille (lignes 1, 5 et 8), Gare de Lyon (RER)

Bus 29, 69, 76, 86, 87, 91, N01, N02, N11, N16

Calculate my routeCar park

Parking Indigo Opéra Bastille 1 avenue Daumesnil 75012 Paris

Book your spot at a reduced price-

Cloakrooms

Free cloakrooms are at your disposal. The comprehensive list of prohibited items is available here.

-

Bars

Reservation of drinks and light refreshments for the intervals is possible online up to 24 hours prior to your visit, or at the bars before each performance.

In both our venues, discounted tickets are sold at the box offices from 30 minutes before the show:

- €35 tickets for under-28s, unemployed people (with documentary proof less than 3 months old) and senior citizens over 65 with non-taxable income (proof of tax exemption for the current year required)

- €70 tickets for senior citizens over 65

Get samples of the operas and ballets at the Paris Opera gift shops: programmes, books, recordings, and also stationery, jewellery, shirts, homeware and honey from Paris Opera.

Opéra Bastille

- Open 1h before performances and until performances end

- Get in from within the theatre’s public areas

- For more information: +33 1 40 01 17 82

Online

Opéra Bastille

Place de la Bastille

75012 Paris

Public transport

Underground Bastille (lignes 1, 5 et 8), Gare de Lyon (RER)

Bus 29, 69, 76, 86, 87, 91, N01, N02, N11, N16

Calculate my routeCar park

Parking Indigo Opéra Bastille 1 avenue Daumesnil 75012 Paris

Book your spot at a reduced price-

Cloakrooms

Free cloakrooms are at your disposal. The comprehensive list of prohibited items is available here.

-

Bars

Reservation of drinks and light refreshments for the intervals is possible online up to 24 hours prior to your visit, or at the bars before each performance.

In both our venues, discounted tickets are sold at the box offices from 30 minutes before the show:

- €35 tickets for under-28s, unemployed people (with documentary proof less than 3 months old) and senior citizens over 65 with non-taxable income (proof of tax exemption for the current year required)

- €70 tickets for senior citizens over 65

Get samples of the operas and ballets at the Paris Opera gift shops: programmes, books, recordings, and also stationery, jewellery, shirts, homeware and honey from Paris Opera.

Opéra Bastille

- Open 1h before performances and until performances end

- Get in from within the theatre’s public areas

- For more information: +33 1 40 01 17 82

Online

Discover opera and ballet in another way

Dive into the Opera world and get insights on opera and pop culture or ballet and cinema. Scan this code to access all the quiz and blindtests on your mobile.

5 min

Die Walküre

The true/false story of Die Walküre

Discover the story of Wagner's opera Die Walküre

DiscoverYou will also like

Partners

-

Grande Mécène de la saison

-

With the exceptional support of Bertrand and Nathalie Ferrier, Élisabeth and Bertrand Meunier

Media and technical partners

-

Radio broadcaster