Synopsis

Listen to the synopsis

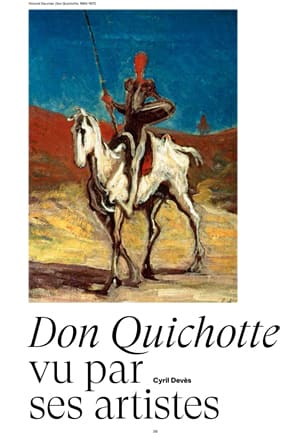

Inspired by Marius Petipa’s choreography, Rudolf Nureyev’s Don Quixote is a true celebration of dance with a Spanish flavour. The soloists and the Corps de Ballet are carried away in ensembles and pas de deux to the strains of a spirited score.

Written in the 17th century, Cervantes’ novel recounts the adventures of Don Quixote, an idealist and bookworm who one day decides to ride across Spain with the naive Sancho Panza.

In Nureyev’s ballet they meet Kitri and Basilio. The two lovers use every trick in the book – from a puppet performance to a fake suicide – to be reunited, despite Kitri’s father’s resistance.

In the end it is Don Quixote who delivers the happy ending after battling windmills and crossing paths with Cupid, Dulcinea and the Queen of the Dryads. The costumes and colourful sets sublimate a vivacious and entertaining work.

Duration : 2h50 with 2 intervals

-

Opening

-

First part 50 min

-

Intermission 20 min

-

Second part 45 min

-

Intermission 20 min

-

Third part 35 min

-

End

Artists

Ballet in a prologue and three acts

Choreography after Marius Petipa

Creative team

Cast

- Thursday 21 March 2024 at 19:30

- Sunday 24 March 2024 at 14:30

- Tuesday 26 March 2024 at 19:30

- Wednesday 27 March 2024 at 19:30

- Friday 29 March 2024 at 19:30

- Saturday 30 March 2024 at 19:30

- Monday 01 April 2024 at 14:30

- Tuesday 02 April 2024 at 19:30

- Thursday 04 April 2024 at 19:30

- Friday 05 April 2024 at 19:30

- Saturday 06 April 2024 at 19:30

- Tuesday 09 April 2024 at 19:30

- Wednesday 10 April 2024 at 19:30

- Thursday 11 April 2024 at 19:30

- Friday 12 April 2024 at 19:30

- Saturday 13 April 2024 at 19:30

- Tuesday 16 April 2024 at 19:30

- Wednesday 17 April 2024 at 19:30

- Thursday 18 April 2024 at 19:30

- Friday 19 April 2024 at 19:30

- Saturday 20 April 2024 at 19:30

- Monday 22 April 2024 at 19:30

- Tuesday 23 April 2024 at 19:30

- Wednesday 24 April 2024 at 19:30

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

Latest update 13 January 2023, cast is likely to change.

The Étoiles, the Premières Danseuses, the Premiers Danseurs and the Paris Opera Corps de Ballet

The Paris Opera Orchestra

Media

Access and services

Opéra Bastille

Place de la Bastille

75012 Paris

Public transport

Underground Bastille (lignes 1, 5 et 8), Gare de Lyon (RER)

Bus 29, 69, 76, 86, 87, 91, N01, N02, N11, N16

Calculate my routeCar park

Parking Indigo Opéra Bastille 1 avenue Daumesnil 75012 Paris

Book your spot at a reduced price-

Cloakrooms

Free cloakrooms are at your disposal. The comprehensive list of prohibited items is available here.

-

Bars

Reservation of drinks and light refreshments for the intervals is possible online up to 24 hours prior to your visit, or at the bars before each performance.

-

Parking

You can park your car at the Indigo Opéra Bastille. It is located at 1 avenue Daumesnil, 75012 Paris.

In both our venues, discounted tickets are sold at the box offices from 30 minutes before the show:

- €25 tickets for under-28s, unemployed people (with documentary proof less than 3 months old) and senior citizens over 65 with non-taxable income (proof of tax exemption for the current year required)

- €40 tickets for senior citizens over 65

Get samples of the operas and ballets at the Paris Opera gift shops: programmes, books, recordings, and also stationery, jewellery, shirts, homeware and honey from Paris Opera.

Opéra Bastille

- Open 1h before performances and until performances end

- Get in from within the theatre’s public areas

- For more information: +33 1 40 01 17 82

Online

Opéra Bastille

Place de la Bastille

75012 Paris

Public transport

Underground Bastille (lignes 1, 5 et 8), Gare de Lyon (RER)

Bus 29, 69, 76, 86, 87, 91, N01, N02, N11, N16

Calculate my routeCar park

Parking Indigo Opéra Bastille 1 avenue Daumesnil 75012 Paris

Book your spot at a reduced price-

Cloakrooms

Free cloakrooms are at your disposal. The comprehensive list of prohibited items is available here.

-

Bars

Reservation of drinks and light refreshments for the intervals is possible online up to 24 hours prior to your visit, or at the bars before each performance.

-

Parking

You can park your car at the Indigo Opéra Bastille. It is located at 1 avenue Daumesnil, 75012 Paris.

In both our venues, discounted tickets are sold at the box offices from 30 minutes before the show:

- €25 tickets for under-28s, unemployed people (with documentary proof less than 3 months old) and senior citizens over 65 with non-taxable income (proof of tax exemption for the current year required)

- €40 tickets for senior citizens over 65

Get samples of the operas and ballets at the Paris Opera gift shops: programmes, books, recordings, and also stationery, jewellery, shirts, homeware and honey from Paris Opera.

Opéra Bastille

- Open 1h before performances and until performances end

- Get in from within the theatre’s public areas

- For more information: +33 1 40 01 17 82

Online

Discover opera and ballet in another way

Dive into the Opera world and get insights on opera and pop culture or ballet and cinema. Scan this code to access all the quiz and blindtests on your mobile.