Prices

Show / Event

Venue

Experience

No result. Clear filters or select a larger calendar range.

No show today.

At the end of the Enlightenment, Jean-Baptiste Lully’s heirs were having difficulty in improving the Opera’s finances. Still, the 18th century was marked by two great composers: Jean-Philippe Rameau and Christoph Willibald Gluck, and by several aesthetic fights. Ballet also underwent many changes, with the decisive contribution of Jean-George Noverre.

Concession and public management

After Lully's death, the Institution underwent a major administrative and financial crisis. The royal privilege passed from hand to hand, but not one director managed to make up for the Opera's deficit.

In 1749, Louis XV gave the Opera's leadership to the City of Paris and so, for a time, the privilege entrusted to an individual who had to bear the financial losses of the theatre at his own risk, disappeared in favour of public management.

With only a gap from 1775 to 1777, this type of management continued until 1780, when the Council of State placed the Opera under the direct supervision of the Royal authority (the ‘Menus Plaisirs du Roi’).

Evolution of the repertoire

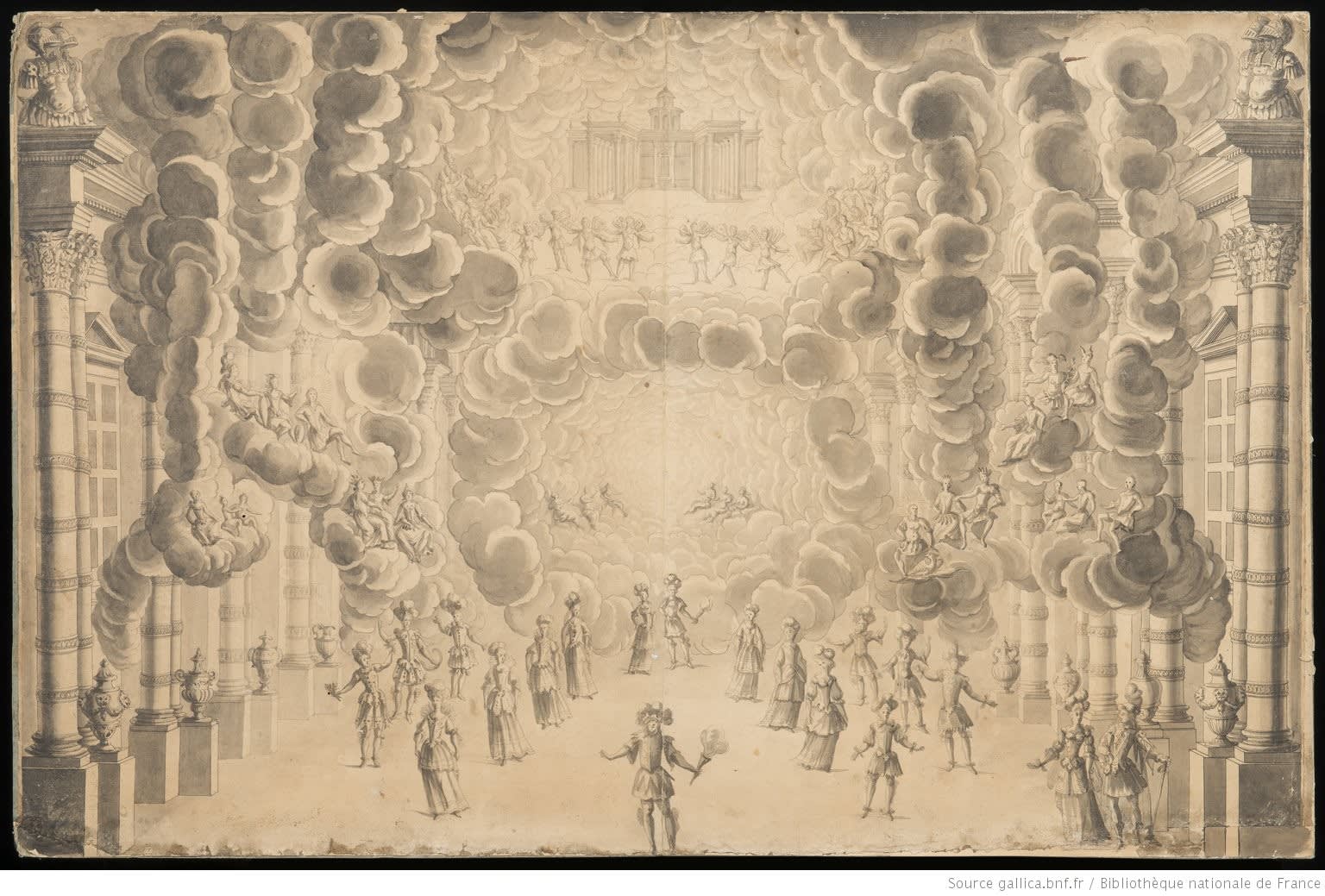

New successes required a renewed repertoire, and thus the lyrical genre progressively evolved towards the opera-ballet, mainly inaugurated with composer André Campra and his L’Europe galante (1697), which gave dance a central place.

The “heroic pastoral”, a genre already featured by Lully in his Acis et Galatée, was revived by André Cardinal Destouches who premiered Issé in 1697. With a plot condensed in three acts and a lighter tone, the work was quite different from the lyric tragedy.

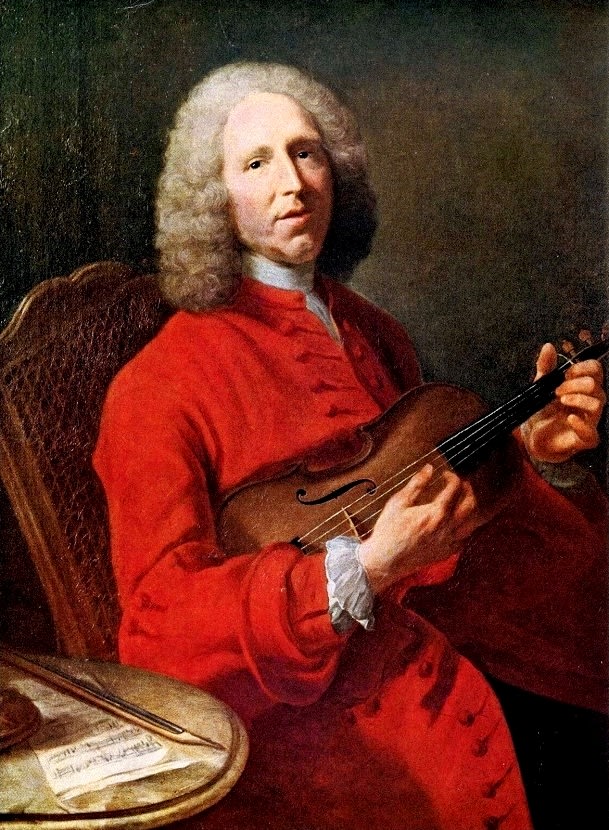

But the 18th century was essentially marked by Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764), who sparked off major aesthetic quarrels.

The “Ramistes” against the “Lullystes”

On 1st October 1733, Jean-Philippe Rameau, who was then 50, premiered his first opera: Hippolyte et Aricie. Though it was a real success, it aroused a huge controversy. The opera’s structure was mainly based on Lully, regarded as the founder of French opera, yet Rameau stood out with his own musical and orchestral originality.

Both camps had their supporters: Rameau and the “Ramistes” against the “Lullyistes”. Setting the old school against the new one, this quarrel was revived with each of Rameau’s creations, such as Castor et Pollux (1737), Dardanus (1739) or his opera-ballet Les Indes galantes (1735), and ended only in 1746.

The Quarrel of the Comic Actors ('la querelle des bouffons')

A second crisis erupted on 1st August 1752, this time sparked by the intermezzo La Serva padrona (The Maid Turned Mistress) by Italian composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, performed by an Italian company at the Paris Opera.

Its appealing musicality seduced critics including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Diderot and Baron von Grimm, who criticised the French style, championed by Rameau and defended by d'Alembert and Madame de Pompadour, for its lack of musicality, its solemn style and stuffy heroes.

The war raged for two years, but it allowed French music to open up to other influences. Rameau continued to dominate the Parisian stage and, until his death, his works were the most played at the Opera.

Marie-Antoinette’s influence

In 1770, Marie-Antoinette married the future King Louis XVI. Unattracted to French music, she sought to impose her former teacher, Christopher Willibald Gluck, who had given her music lessons in Austria as a child.

The composer, who had already theorised his ideas in the prolog of Alceste (1767), created on 19 april 1774 at the Royal Academy of Music his Iphigénie en Aulide, or a “lyrical drama” in which he managed to synthesise both the vocal Italian and the solemn French styles.

His success drove him to create a French version at the Paris Opera of Orphée et Eurydice (1774), and then of Alceste (1776). But, for the third time, a new controversy divided two camps, resurrecting the quarrel between French and Italian operas: the Gluckists, against the supporters of Niccolò Piccini, the Piccinistes.

As for ballet, Marie-Antoinette imposed Jean-Georges Noverre (1727-1810) as ballet master in 1776. This dancer, choreographer and dance theoretician advocated for an “expressive dance in action”. For him, pantomime had a key and dramatic role to play in dance technique, and ballet should be an independent artistic discipline, and not just a mere decorative art for opera’s interludes. The first ballet-pantomime performed at the Paris Opera was his Médée et Jason (1776), which was a great success.

Special characters!

If Louis XIV proclaimed “L’État, c’est moi !” (“I am the State!”), Jean-Baptiste Lully could easily have declared: “I am the opera”.

As for the dancer Vestris, the ballet master of the Académie Royale de Musique, he would claim: “There are only two great men alive today: myself and Voltaire”.