Prices

Show / Event

Venue

Experience

No result. Clear filters or select a larger calendar range.

No show today.

© BnF

Saint-Saëns and stage

Saint-Saëns - Partie 3

Phryné. Esquisse de décor pour l’acte II : « Intérieur grec ». Par Philippe Chaperon, 1893. Dessin à la plume, aquarelle, gouache et collage, 31,2 x 20,5 cm. BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l'Opéra BnF

Affiche pour Le Timbre d’argent annonçant la représentation du 23 février 1877 au Théâtre-Lyrique (Gaîté) à Paris. Lithographie par Prudent Leray, tirage en noir, 60 x 80 cm. BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l'Opéra, Affiches illustrées. BnF

Maquette de costume pour le rôle d’Étienne Marcel dans Étienne Marcel. Projet pour les représentations du Théâtre du Château d’eau, octobre 1884 par Jules Marre. Aquarelle, 15,6 x 23,8 cm. BnF, département des Arts du spectacle, BnF

Maquette de costume pour le rôle du Dauphin dans Étienne Marcel. Projet pour les représentations du Théâtre du Château d’eau, octobre 1884. Par Jules Marre. Aquarelle, 15,6 x 24,2 cm. BnF, département des Arts du spectacleBnF

BnF

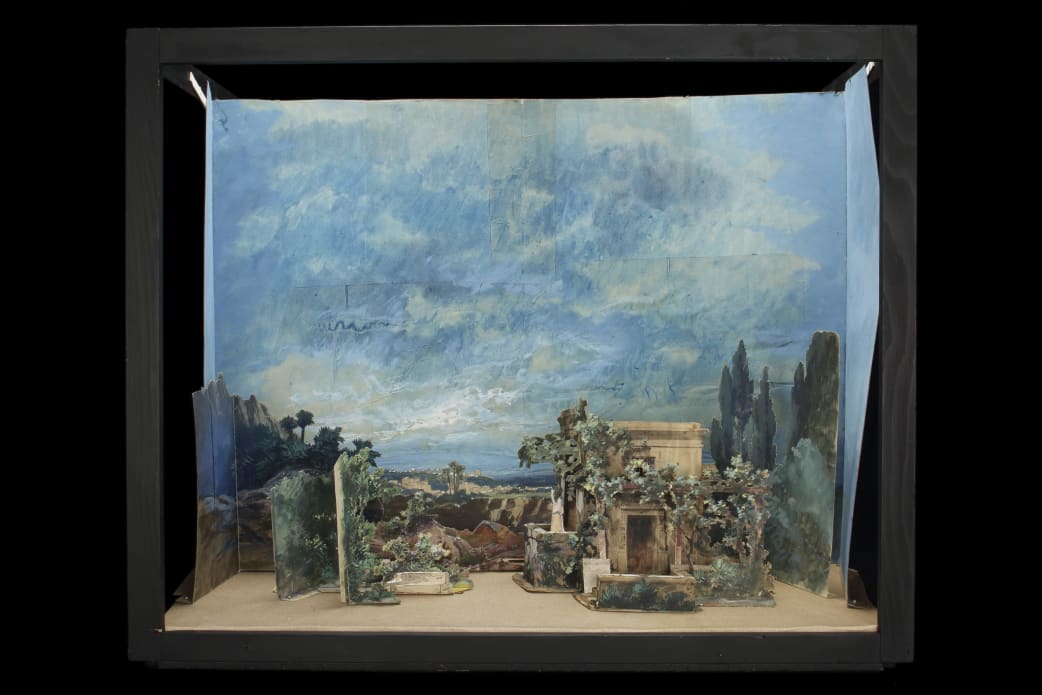

Maquette de décor en volume pour Samson et Dalila, acte II : « La maison de Dalila dans la vallée de Soreck ». Par Eugène et Amable Gardy, 1892. BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l'Opéra BnF

BnF

Emmanuel Lafarge et Amélie Bossy en costumes de scène dans les rôles-titres lors de la première représentation de Samson et Dalila au Théâtre des arts de Rouen, 3 mars 1890. Photographie en noir et blanc, par Bencque & Cie. BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l'OpéraBnF

BnF

BnF

Jean Lassalle, créateur du rôle d’Henry VIII dans Henry VIII, en costume de scène. Photographie par Bencque & Cie, 1883. BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l'OpéraBnF

Henry VIII. Maquette de costume pour le rôle d’Henry VIII. Par Eugène Lacoste, octobre 1882. Dessin à la plume et gouache, 31 x 40 cm. BnF, Bibliothèque-musée de l'OpéraBnF

BnF

“Let us therefore have the courage to say it: however great the interest of orchestral music – and it is not me who shall be accused of contesting this – the real musical life is found at the theatre.”

A great interpreter and composer regarded as one of the “symphonists”, Saint-Saëns had to overcome a great many hurdles to access the opera house, where he longed to prove himself. Classical or historical subjects provided him with a framework that suited him: one with which the public was already assumed to be familiar, on which he could harness all the complexity of human nature, excite crowds and stage highly dramatic situations. But he faced his share of criticism, levelled against the chosen subjects of his librettos and the classicism of his style.

Vocal works accounted for half of his tremendous output: songs, choruses, cantatas, odes, hymns or oratorios surround 13 operatic works: La Princesse Jaune (1872), Samson et Dalila (1877), Le Timbre d’argent (1877), Étienne Marcel (1879), Henry VIII (1883), Proserpine (1887), Ascanio (1890), Phryné (1893), Frédégonde (1895) left unfinished by Guiraud, Les Barbares (1901), Hélène (1904) and L’Ancêtre (1906), Déjanire (2nd version, 1911), in addition to Déjanire (1st version, 1898) and Parysatis (1902), composed for an open-air performance in Béziers. Saint-Saëns also had firm theories about opera and was intent on putting these into practice. He was often at loggerheads with theatres and his writings reflect this: “And there are people who are forever on my back to write operas. I’ve already done too many for goodness’ sake!!!….. And when they are not performed, it’s awful; when they are performed it’s even worse! And the worst thing of all is having to deal with theatre directors.”