Preview for young adults

Under 28 years old? At noon, book your €10 seats for the opera Don Quichotte by Jules Massenet.

Preview for young adults

Under 28 years old? At noon, book your €10 seats for the opera Don Quichotte by Jules Massenet.

Currently at the Opera

See the calendarNews

See all the news-

Learn more

19 April 2024

New

Cast change: Don Quichotte

-

Learn more

08 April 2024

Tous à l'Opéra ! Édition 2024

-

Learn more

26 March 2024

Bleuenn Battistoni nominated Danseuse Étoile de l'Opéra national de Paris

-

Learn more

27 March 2024

Prix de l'Arop season 2022/2023

-

Learn more

20 March 2024

The artistic programme 24/25 is online !

-

Learn more

18 March 2024

Kinoshita Group Co., Ltd. and the Paris Opera are glad to announce the signature of a major partnership

-

Learn more

08 March 2024

Cast change: Don Quichotte

-

Learn more

06 March 2024

The Exterminating Angel: cast change

-

Learn more

24 February 2024

Anna Ringart obituary

-

Learn more

22 February 2024

La Traviata: cast change

Life at the Opera

-

Video

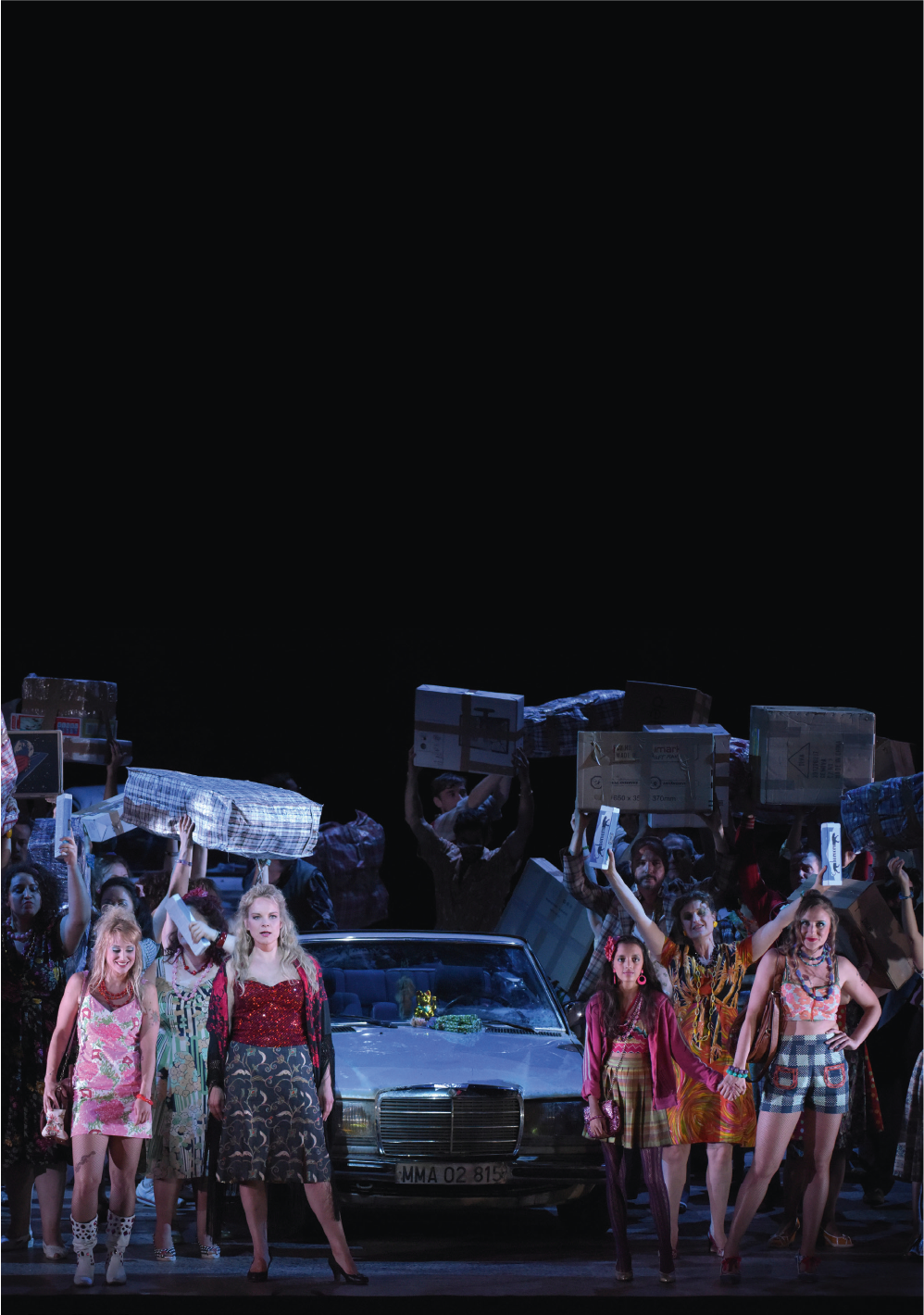

Street Scenes in rehearsal

Watch the video

-

Video

Draw-me Médée

Watch the video

-

Video

Podcast Médée

Watch the video

-

Video

From chrysalis to butterfly: Paris Opera Ballet School students rehearse for annual show

Watch the video

-

Video

Draw-me Don Quixote

Watch the video

-

Video

Absolute revenge - Interview with David McVicar

Watch the video

-

Video

Draw-me Salome

Watch the video

-

Video

Giselle, romantic and sincere

Watch the video

-

Video

Draw-me Giselle

Watch the video

The Opera in streaming

Watch our greatest performances wherever you are with POP, the Paris Opera's streaming platform.

Free trial 7 days

-

03h40

Live Saturday, June 29 at 7:00 p.m.

03h40

-

01h00

Jiří Kylián

Ballet

01h00

-

02h05

02h05

-

00h37

00h37

-

01h22

01h22

-

00h31

L'Opéra en Guyane - Episode 4

Documentary

00h31

-

02h11

02h11

-

02h09

02h09

-

03h33

03h33

-

02h21

02h21

Immerse in the Paris Opera universe

Business Space

-

Patronage and Sponsorship

-

Your public relations operations

-

Rental of spaces and filming

-

Licensing program, advertising space and cultural engineering

-

Galas

Place de l’Opéra

75009 Paris

Place de la Bastille

75012 Paris

Back to top